Blogs

The original first appeared on: https://smartsexresource.com/health-providers/blog/201807/optimal-strategies-diagnosis-and-treatment-acute-or-chronic-hepatitis-b

Optimal Strategies for diagnoses and treatment of acute and chronic hepatitis B infection in British Columbia

July 31, 2018 by Mawuena Binka, Research Associate, university of British Columbia and BC Centre of Disease Control

Background

Hepatitis B (HBV) is a vaccine-preventable infection. People who have not been vaccinated, however, may become infected through contact with the body fluids of an HBV-infected person.

While the early stages of HBV infection may be characterized by non-specific symptoms in some, many people are asymptomatic. Consequently, people living with acute HBV may progress to chronic illness and remain undiagnosed for years until advanced liver disease and liver cancer have developed.

Early diagnosis through HBV screening, and early treatment of HBV infections, is necessary to reduce the risk of complications among those affected.

Hepatitis B in British Columbia

British Columbia (BC) reported five new cases of acute HBV in 2016; a record low attributable to province-wide childhood vaccination programs that have been in place for over two decades. However, more than a thousand new cases of chronic HBV are reported each year.

In BC, 50% of people living with chronic HBV and decompensated cirrhosis or liver cancer are diagnosed late in the course of their infection; many are diagnosed alongside or after diagnosis with advanced liver disease. This highlights the need for more effective HBV screening programs.

Purpose of research

Differences in the demographics and risk behaviors of people diagnosed with acute or chronic HBV infections may impact the public health interventions targeted at either population.

Using data from the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort, we assessed the characteristics of individuals diagnosed with acute or chronic HBV infection between 1990 and 2015. We identified the factors associated with acute or chronic HBV infection to inform prevention and screening programs in BC.

Key findings

- 46,498 of the 1,058,056 (4.4%) study participants were HBV-positive, of which 2,015 (4.3%) were diagnosed with acute HBV, and 44,483 (95.7%) with chronic HBV.

- Acute HBV infection, indicative of viral transmission, was diagnosed predominantly among males (71%), people between the ages of 25 and 34 (32%), White individuals (78%), socioeconomically disadvantaged people, and individuals with a history of substance use (alcohol dependence or injection drug use) or co-infection with HIV or hepatitis C.

- Individuals diagnosed with chronic HBV infection were predominantly older, East Asian (60%), with no history of substance use or co-infection.

- After adjusting for confounding variables, East Asians had 12 times greater odds of being diagnosed with chronic HBV infection than Whites, and these odds increased with increasing socioeconomic deprivation.

Implications

These findings highlight distinct risk patterns for individuals with acute and chronic HBV infection and underscore the need for different strategies to prevent, diagnose and treat HBV within these groups.

Optimal care for acute HBV requires the integration of HBV prevention, screening, and treatment programs with programs for mental health, addiction and other blood-borne infections. In contrast, managing chronic HBV requires screening programs for early diagnosis and treatment among at-risk ethnic groups, including foreign-born East and South Asians, with low prevalence of traditional risk factors.

For more information

This study was recently published in World Journal of Gastroenterology:

Binka M, Butt ZA, Wong S, Chong M, Buxton JA, Chapinal N, Yu A, Alvarez M, Darvishian M, Wong J, McGowan G, Torban M, Gilbert M, Tyndall M, Krajden M, Janjua NZ. Differing profiles of people diagnosed with acute and chronic hepatitis B virus infection in British Columbia, Canada. World J Gastroenterol. 2018 Mar 21;24(11):1216-1227. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i11.1216.

https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i11/1216.htm

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the BC Centre for Disease Control.

The original first appeared on: https://smartsexresource.com/health-providers/blog/201708/harm-reduction-to-prevent-hepatitis-c-reinfection-evidence-largest

Harm reduction to prevent Hepatitis C reinfection: evidence from the largest study to-date

Aug 25, 2017 by Nazrul Islam, University of British Columbia and Harvard University

Background

The cure rate of Hepatitis C (HCV) treatment with newer direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents is very high (>95%). These treatments are also well-tolerated, bringing significant optimism to expanding treatment options to include more people at risk, particularly people who inject drugs (PWID). Barriers to accessing treatment by PWID have been widely reported, which has fueled both ethical and public health concerns.

HCV reinfection

People remain at risk of reinfection even after clearing an HCV infection spontaneously or following a successful course of HCV therapy. The concern of HCV reinfection is paramount, worsened by the fact that no effective vaccine against HCV exists, and the DAAs are prohibitively expensive (treatment cost ranges between $45,000-$110,000 CAD per person).

As HCV treatment in British Columbia is publicly covered through the BC Medical Services Plan, public health policy faces an unpleasant dilemma. While more PWID should be offered HCV treatment (from both an ethical and treatment-as-prevention point of view), these are the people who are at most risk of HCV reinfection.

To get the most out of publicly-funded HCV therapy, more evidence is needed on how to minimize HCV reinfection among PWID. There is a dearth of data around HCV reinfection, particularly from larger cohort studies with longer follow-up times.

Preventing reinfection

The BC Centre for Disease Control recently published the largest study to-date, describing potential predictors of HCV reinfection and the role of harm reduction interventions (e.g., opioid substitution therapy and mental health counseling) in preventing HCV reinfection.

This 19-year follow-up study, based on the data from the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort, identified 5,915 cases of HCV that cleared their first infection either spontaneously or after successful HCV therapy.

Cases were followed up for a median of 5.4 years (interquartile range: 2.9-8.7). The study also collected data on age, sex, birth cohort, year of HCV diagnosis, HIV coinfection, risk behaviours (injection drug use and alcohol dependence), harm-reduction interventions (opioid substitution therapy and mental health counselling), and socioeconomic deprivation.

Key findings

- Of 5,915 cases, 3,690 (62%) cleared their first infection spontaneously and 2,225 (38%) achieved treatment-induced clearance (i.e., sustained virological response (SVR)).

- Overall, 452 (8%) cases developed reinfection. The rate was significantly higher among the spontaneous clearance group (11%; n= 402) compared to the SVR group (2%; n=52).

- After adjusting for other confounders, risk of HCV reinfection was higher in the spontaneous clearance group, those coinfected with HIV, and PWID.

- Among those with a history of current injection drug use, opioid substitution therapy was significantly associated with a 27% lower risk of reinfection, while engagement with mental health counselling services was associated with a 29% reduction in reinfection risk.

Policy implications

The findings from this study indicate that HCV treatment, complemented with opioid substitution therapy and mental health counselling, could reduce HCV reinfection risk among PWID. These findings also support policies of post-clearance follow-up of PWID, and provision of harm-reduction services to minimise HCV reinfection and transmission. A significant reduction in HCV reinfection may have substantial economic savings in the era of expensive DAA.

For more information

This study was recently published in the Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/langas/article/PIIS2468-1253(16)30182-0/fulltext

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship.

Co-authors: Mel Krajden, Jean Shoveller, Paul Gustafson, Mark Gilbert, Jane A Buxton, Jason Wong, Mark W Tyndall, and Naveed Z Janjua

Categories: New knowledge

The original first appeared on: http://blog.catie.ca/2017/07/28/hepatitis-c-cascade-of-care-an-essential-tool-for-monitoring-progress-towards-hcv-elimination/?utm_source=tw&utm_medium=socmed&utm_campaign=072817&utm_content=en

Hepatitis C cascade of care: An essential tool for monitoring progress towards HCV elimination

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major public health problem. Worldwide, about 70 million people are living with hepatitis C virus infection, with a higher prevalence in developing countries. In Canada, 210,753 to 461,517 people are infected with HCV, and an estimated 20 to 40 per cent of infections remain undiagnosed. Those born during the period of 1945 until 1965 have the highest rates of infection and, having acquired the virus decades ago, are now increasingly being diagnosed with serious liver-related illnesses, including liver failure and liver cancer and non-liver related illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and kidney disease.

While the new highly effective hepatitis C treatments are expected to turn the tide of increasing liver-related problems and early death, for any hepatitis C treatment program to have a major impact, patients have to be diagnosed, connected to the right kind of care, and begin (and complete) treatment. Accordingly, we need to monitor the progress of patients across their illness and care journey (also known as the cascade of care) − to evaluate the effectiveness of our hepatitis C care and treatment programs.

In the Global Health Sector Strategy, the World Health Organization (WHO) has set bold goals for HCV. The Strategy calls for eliminating viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030, a goal that would reduce HCV-related deaths by 65 per cent and new infections by 90 per cent by 2030. WHO is using the cascade of care to monitor the progress of countries towards these goals.

So what is the hepatitis C cascade of care? WHO defines the cascade of care as the continuum of services that people living with hepatitis should receive as they go through various stages, from testing to diagnosis, to treatment to cure, to chronic care, if needed. This serves as a tool for monitoring the progress of patients at a clinic, in a city, a province or in a country. Monitoring the population affected by HCV across stages of a cascade of care at a broader population level provides a measure of hepatitis C programming effectiveness and identifies gaps in services and access.

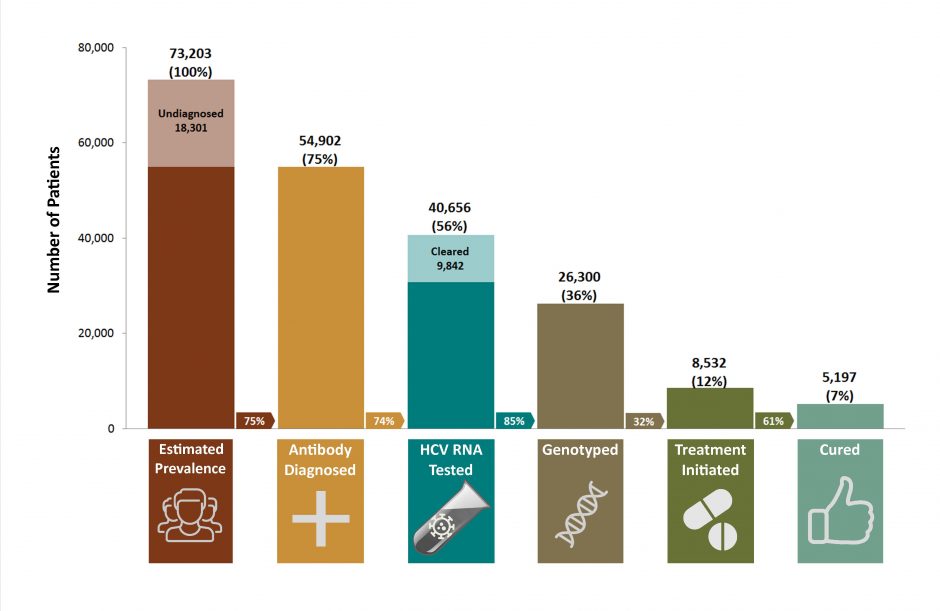

British Columbia has constructed a hepatitis C cascade of care at the provincial level through the integration of data on hepatitis C screening and confirmatory testing, medical visits, hospitalization and hepatitis C treatments in the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort . The baseline cascade showed that 73,203 people were HCV antibody positive[1] in B.C. in 2012 (undiagnosed: 18,301 or 25 per cent; diagnosed: 54,902 or 75 per cent). Of these HCV-positive people, 40,656 people or 56 per cent had HCV RNA testing; 26,300 people or 34 per cent had genotype testing; 8,532 people or 12 per cent had received interferon-based therapy and 5,197 people or 7 per cent were cured (also known as a sustained virological response or SVR). Males, people in older birth cohorts, and those co-infected with hepatitis B were less likely to undergo HCV RNA testing. Among those with chronic HCV infection, 32 per cent had received liver-related care. Retention in liver care was more likely in those with HIV co-infection, cirrhosis, and drug/alcohol use and less likely in males and those co-infected with hepatitis B.

This cascade highlighted points across the cascade where people were falling through the cracks for various reasons. Not all diagnosed individuals had confirmatory RNA and genotype testing. Having automatic RNA and genotype testing at the laboratory for individuals testing positive for anti-HCV could bridge this gap. This way health-care providers ordering anti-HCV tests would have full information regarding HCV infection status at the time of their patient’s next visit and could decide next steps in terms of HCV treatment, if the person is RNA positive.

Other gaps, such as low treatment uptake among people with HIV co-infection and substance use, were related to the perception of physicians regarding poor tolerability and adherence to long-term treatment with interferon. Highly tolerable and effective direct-acting antivirals are expected to bridge these gaps. Data from British Columbia and other places show that treatment uptake for people with HIV co-infection has been improving, though some gaps remain for people who inject drugs.

The data uncovered by the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort highlights the need and importance of monitoring the progress of HCV programs across the cascade of care for entire populations in order to address gaps in care. Other provinces, and Canada as a whole, should invest in bringing together the necessary data needed for constructing cascades of care to monitor all individuals living with hepatitis C across their illness and care journey. Clinical care data generated during contacts with health-care systems are untapped resources that Canadians have already paid for, and could transform HCV care. The examination of data will also allow the health sector to monitor disparities across population groups (ethnicity, people who use drugs, low socioeconomic status) or geographic areas (rural and remote) in provision of hepatitis-related care.

Naveed Janjua, MBBS, DrPH, is a Senior Scientist at BC Centre for Disease Control and Clinical Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia.

[1] Testing for hepatitis C involves three steps. 1. A hepatitis C antibody test. If someone has hepatitis C antibodies in their blood it means the hepatitis C virus has been in there body at some point. 2. A hepatitis C RNA test. This test checks for the genetic material of the virus. If it is present in the blood this means someone currently has hepatitis C virus. 3. A genotype test. This test checks what type (or genotype) of hepatitis C virus a person has.

The original first appeared on: http://smartsexresource.com/health-providers/blog/201608/epidemiology-new-versus-prevalent-hepatitis-c-infections-canada-bc

Epidemiology of new vs. prevalent hepatitis C infections in Canada: BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort

Aug 3, 2016 by Margot Kuo, Epidemiologist, Clinical Prevention Services, BCCDC

Introduction

In BC, at least 50,000 people are currently living with active hepatitis C (HCV) infection.[1,2] Left untreated, individuals with HCV have 5 times higher risk of dying from any cause and 20 times higher risk of dying from liver-related causes than uninfected persons.[3]

Newer, well-tolerated drugs (direct acting antivirals) have improved treatment success with cure rates approaching 95% while also reducing side effects. This presents new opportunities to prevent progressive liver disease in the population. However, treatment alone may not be sufficient for all individuals living with HCV. Some individuals may benefit from complementary programs to prevent liver damage and/or reinfection with HCV.

A large data platform, the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC), has been assembled to assess and monitor HCV disease burden, including important co-infections such as HIV, tuberculosis, and hepatitis B and risk factors for liver damage and HCV re-infection.[4]

Based on the BC-HTC, the epidemiology of new and prevalent HCV infection has been described for BC.

Methods

The BC-HTC includes all individuals, since about 1990, that have either tested for HCV or HIV at the BCCDC Public Health Laboratory, or have been reported to public health as a case of HCV, HBV, HIV/AIDS, or active TB. This cohort of over 1 million people is linked with medical visits, hospitalizations, prescription drugs, cancers, and deaths.[4]

We compared two groups of HCV positive cases in terms of age, gender, markers of substance use and mental illness, and social and material deprivation.

HCV positive cases are divided into prevalent cases (those that tested HCV positive at their first test on record), and seroconverters (those that tested positive after a prior negative test). In seroconverters, infection occurred in the interval between the prior negative and first positive test, which suggests that there were risk factors for HCV acquisition during that time. In prevalent cases the timing of infection is unknown but more likely to be decades ago, based on previous explorations of HCV testing patterns.

Summary of evidence

Of the 1,132,855 individuals in the cohort, 67,726 were HCV cases as of the end of 2013. Of these, 11,954 (17.7%) had died.

Comparing the HCV groups, select findings include (see below infographic):

Prevalent cases: Older; more stable living conditions; more liver disease and age-related health issues

- 88% of all cases. the majority of which (73%) were born before 1965

- high rates of liver-related illness and death

- lower prevalence of illicit drug use, mental illness, and HIV coinfection at time of HCV diagnosis

- lower prevalence of problem alcohol use than seroconverters. However, even low to moderate alcohol use has implications for liver disease progression in HCV infected persons.

Seroconverters: Younger; living with multiple vulnerabilities

- 12% of all cases, the majority of which (74%) were born after 1965

- more likely to be coinfected with HIV and be socioeconomically marginalized at time of diagnosis

- high proportion of this group are living with serious mental illness and/or had evidence of illicit drug use

Infographic: The twin HCV epidemics in Canada

Implications for practice

There are clear differences between older individuals diagnosed with HCV at first test (prevalent cases), compared with younger individuals diagnosed with HCV following previous negative test(s) (seroconverters).

Seroconverters can benefit from a comprehensive approach that integrates:

- harm reduction

- treatment and support for mental illness and dependence/addictions

- treatment for HCV and co-infections, like HIV

- stable housing and income

This approach will not only prevent HCV reinfection, but will also improve quality and quantity of life.

In contrast, prevalent cases have comparatively lower rates of illicit drug use, mental illness, alcohol use, and HIV coinfection. However, they require immediate linkage to care and assessment for treatment to prevent end-stage liver disease and premature death. Even the moderate prevalence of problem alcohol use suggests that awareness of HCV and strategies to reduce liver damage in infected persons requires improvement.

For further information

See the full publication for more details: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/16/334

See the BC-HTC website for further information (patients and health care providers): http://hepatitiseducation.med.ubc.ca/

Acknowledgements

Dr. Naveed Janjua, Dr. Jason Wong, and Maria Alvarez, Clinical Prevention Services, BCCDC

References

- British Columbia Centre for Disease Control. British Columbia Annual Summary of Reportable Diseases 2014. Available at: http://www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Statistics%20and%20Research/Statistics%20and%20Reports/Epid/Annual%20Reports/AR2014FinalSmall.pdf

- Janjua N, Kuo M, Yu A, Wong S, Alvarez M, Krajden M. The BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort: The population level hepatitis C Cascade of Care in British Columbia, Canada. Conference Presentation at: EASL: The International Liver Congress 2016. Barcelona, Spain. April 13-17, 2016.

- Yu YW, Spinelli JJ, Cook DA, Buxton JA, Krajden M. Mortality among British Columbians testing for hepatitis C antibody. 2013. BMC Infectious Diseases. DOI: 10.1186/1471-3458-13-291. Available at: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-291

- Janjua NZ, Kuo M, Chong M, Yu A, Alvarez M, Cook D, Armour R, Aiken C, Li K, Mussavi Rizi SA, Woods R, Godfrey D, Wong J, Gilbert M, Tyndall MW, Krajden M. Assessing Hepatitis C Burden and Treatment Effectiveness through the British Columbia Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC): Design and Characteristics of Linked and Unlinked Participants. 2016. PLOS ONE. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0150176

The original first appeared on: https://smartsexresource.com/health-providers/blog/201305/current-status-hcv-epidemic-british-columbia-and-canada

The current status of the HCV epidemic in British Columbia and Canada

May 8, 2013 by Margot Kuo, Epidemiologist, Clinical Prevention Services, BCCDC

Background

Prevalence and incidence are two basic measures of disease frequency used to inform our response to the Hepatitis C (HCV) epidemic. Prevalence is the total number of people living with chronic HCV infection, while incidence is the number of new infections that occur in that year.

HCV surveillance in British Columbia relies on diagnoses of HCV in BC, which are looked at two ways:

- The number of new HCV diagnoses reported each year or first-time HCV positive individuals (reactive for antibody to hepatitis C virus or anti-HCV positive); and

- The number of acute cases - new positives with a negative anti-HCV test on record within the prior 12-month period.

These data are imperfect estimates because they only include individuals who have gone for testing, and tests can be done years after initial infection. For HCV incidence, looking at acute cases is a reasonable estimate, but these trends are also influenced by testing behavior (and are more likely to reflect people who test for HCV more frequently).

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) released a surveillance report summarizing hepatitis C in Canada from 2005 - 2010, based on based multiple data sources. This includes the last release of modeled estimates of HCV prevalence and incidence from 2007. Below we describe findings from the Canadian surveillance report and provide the most recent HCV diagnosis trends from British Columbia surveillance data.

Findings

As a chronic condition, HCV prevalence increases over time as cases accumulate. To understand the scope of problem, in 2007, a model was developed to estimate the number of HCV cases in Canada.

- It was estimated that 242,521 people were living with HCV in Canada, corresponding to a prevalence of 0.8% of the general population (Table 1). The prevalence of HCV among males was 1.6 times higher than among females.

- Incidence was modeled at 0.026% or about 8000 persons with newly-acquired infection in 2007. Incidence among males was higher than females and more than three quarters (83%) of incident infections were among persons who inject drugs (PWID).

The annual numbers and rates of laboratory confirmed infections (anti-HCV testing) reported to the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS) decreased between 2005 and 2009 from 13,017 cases in 2005 to 11,357 in 2009, corresponding to a rate of 40.4 per 100,000 in 2005 to 33.2 per 100,000 in 2009 for Canada. While BC rates are also decreasing, rate of new HCV diagnoses in BC is still higher than most other provinces and the national average (Figure 1).

Incidence in BC, as represented by rates of acute cases, has been decreasing since 2008 (Figure 2). Increases in testing volume (over 130,000 persons tested for hep C in 2011) and repeat testing behaviour (testing more than once) have helped to improve this estimate over time.

Interpretation and implications

The decreasing trend in hepatitis C case reports in British Columbia and Canada is thought to be due to a reduction in transmission/incidence related to decrease in illicit drug injection use and/or low numbers of susceptible (uninfected) persons in the key risk population, PWID. There are various HCV risk groups with varying rates of HCV infections. While PWID are a major contributor to the pool of HCV infected individuals in Canada, other risk factors include:(1)

- history of haemodialysis,

- receipt of blood products before 1992 or clotting factors before 1988,

- exposure to blood of high risk individual,

- incarceration,

- unregulated tattoos,

- immigration from a high-prevalence country and

- those presenting with HIV and/or persistently elevated liver enzymes (AST).

While current BC specific estimates of HCV prevalence are not available, there may be 60,000 to 80,000 persons infected with HCV in BC, many unaware of their infection. A recent study of British Columbians who underwent anti-HCV testing found high death rates in HCV positive individuals due to progressive liver disease as well as risks related to drug use, street involvement and poverty.(2) In 2011, about one in three HIV positive individuals in BC were also infected with HCV.(3) All of this suggests that British Columbians with hepatitis C have a spectrum of risks, needs, and health outcomes requiring very different prevention and treatment approaches.

At this time, there are multiple initiatives underway to improve provincial HCV and HIV surveillance data and derived estimates by incorporating other information that would confirm infection and link to important health outcomes, such as treatment and mortality, as well as inform prevention initiatives.

Further information

National estimates are presented in more detail in Hepatitis C in Canada: 2005-2010 Surveillance Report.

Provincial estimates of Hepatitis C rates can be found in British Columbia Annual Summary of Reportable Diseases, 2011.

Notes

PHAC = Public Health Agency of Canada

BCCDC = British Columbia Centre for Disease Control

CNDSS = Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance Systems

PWID = Persons who inject drugs

Acknowledgements

- Mark Gilbert, Physician Epidemiologist, Clinical Prevention Services, BCCDC

- Naveed Janjua, Hepatitis Surveillance Lead, Clinical Prevention Services, BCCDC

- Travis Salway Hottes, Epidemiologist, Clinical Prevention Services, BCCDC

References

- The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. The Reproductive Care of Women Living with Hepatitis C Infection. SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2000.

- Yu A, Spinelli JJ, Cook D, Buxton JA, Krajden M. Mortality among British Columbians testing for hepatitis C antibody. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:291.

- Klein MB, Rollet KC, Saeed S, Cox J, Potter M, et al. HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection in Canada: challenges and opportunities for reducing preventable morbidity and mortality. HIV Medicine. 2013;14:10-20.

The original first appeared on: http://pacificaidsnetwork.org/2017/03/29/the-hepatitis-c-care-cascade-from-diagnosis-to-care-and-treatment-in-british-columbia/

The Hepatitis C Care Cascade: From Diagnosis to Care and Treatment in British Columbia

Posted On: Wednesday, March 29th, 2017

At the PAN Fall Conference, we learned from Dr. Lianping (Mint) Ti about short-course direct-acting antiviral (DAA) drugs for hepatitis C (HCV). These well-tolerated drugs have demonstrated cure rates of 95% and have been available in British Columbia (BC) since 2014, but their dispensation has been limited to individuals with advanced liver disease due to their high cost.

Findings from a recently published paper on the population level cascade of care for HCV in BC demonstrate the need for greater access to liver care and treatment for individuals living with HCV. According to Dr. Naveed Janjua and his colleagues, data from the BC Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC; click here for more information about the cohort) indicates that as of 2012, only 32% percent of the 54,902 people diagnosed with HCV in BC had accessed liver care. Of these diagnosed individuals, only 12% had initiated treatment for hepatitis C and only 7% had achieved a sustained virologic response, defined as an undetectable HCV RNA level measured twelve weeks after completing treatment.

It is also important to note that Janjua and his colleagues estimate that as of December 31, 2012, 18,301 residents of BC were HCV antibody positive but undiagnosed. While it may seem surprising that an estimated 25% of HCV infections in BC are undiagnosed, Janjua et al. cite a 2011 paper by Maxim Trubnikov and colleagues from the Public Health Agency of Canada that suggests 20–44% of HCV infections in Canada are undiagnosed. These statistics illuminate the need for a testing strategy to reach those who are undiagnosed and, as a result, unlinked to care.

Janjua et al.’s findings on the cascade of care for people living with both HIV and HCV also demonstrate the need for accessible interventions. While HIV and HCV co-infected individuals are 6% of the 52,902 people diagnosed with HCV in BC, they are 10%, or 957 people, of the group of people accessing liver care. Of this 10%, however, only 5%, or 408 people, have ever been dispensed treatment. These numbers demonstrate that about 50% of individuals in the co-infected group fall off the cascade of care between these stages, highlighting the gaps that exist between a positive HCV diagnosis and retention in care and treatment.

Fortunately, options for treatment are about to become more accessible for individuals living with HCV in BC, Ontario and Saskatchewan. In February 2017, the BC Ministry of Health announced that thousands of British Columbians living with hepatitis C will have better access to treatment as a result of negotiations brokered by the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA) to improve the costs of these drugs for the BC, Ontario and Saskatchewan governments. Starting around March 21, 2017, physicians in BC can apply on behalf of their patients for coverage to a set of more effective HCV drugs.

In March 2018, coverage restrictions related to disease progression will be lifted completely and BC PharmaCare will provide coverage for any British Columbian living with chronic hepatitis C regardless of the type or severity of their disease. In their paper, Janjua and his colleagues explained how access to drugs such as these are “expected to be a game changer in preventing progressive liver disease.”

We can only hope that access to these better-tolerated drugs will help close the gap between diagnosis, care, and treatment for individuals living with HCV in British Columbia, Ontario and Saskatchewan. As Janjua and his colleagues remind us, “for these drugs to have major population-level impact on morbidity and mortality, screening efforts must reach undiagnosed individuals, diagnosed individuals must be linked with care and people remain engaged with care to be assessed for and receive treatment.”